|

“FENWAY'S BEST PLAYERS”  |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

BILL LEE (1969-1978) … Lee spent his first ten Major League seasons pitching for the Boston Red Sox, winning 94 games. Beginning as a reliever (only starting in nine of his first 125 appearances), he posted a 9-2 season in 1971. After being converted to a starter under Eddie Kasko in 1973, he reeled off three 17-win seasons in a row from 1973 through 1975. He was second only to Luis Tiant in wins the first two years and third to Tiant and Rick Wise in 1975. He pitched exceptionally well in Games Two and Seven of that year's World Series, leaving with games tied in the late innings both times. He started off the 1978 season at 7-1 and then 10-3, but a stormy relationship with manager Don Zimmer cost him and the team, and he dropped seven decisions in a row. He was finally banished to the bullpen without a chance to win even the one additional game that would have handed Boston the pennant. After being traded to Montreal, Lee won 16 games the next year. He was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2008. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

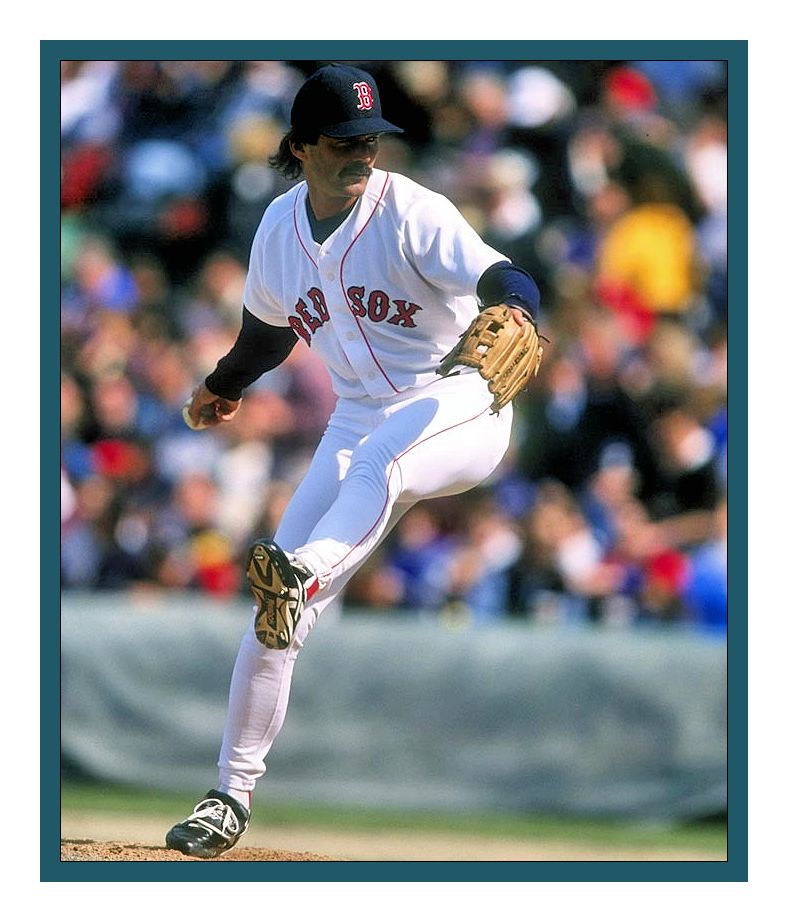

BRUCE HURST (1980-1988) … A Red Sox first-round pick in 1976, Bruce Hurst started his career slowly but wound up winning 88 games for the team, with six seasons of double-digit wins from 1983 through 1988. His best season of all was likely his last, 18-6 with a 3.66 ERA (though rivaled by his 13-8, 2.99 year in 1986). Both years saw the Red Sox venture into Postseason play. In both 1984 and 1988, Hurst led the Red Sox in wins. Hurst couldn't have been much better in October baseball in 1986. He was 1-0, winning Game Two of the ALCS, and 2-0 in the World Series, winning Games One and Five and throwing five shutout innings in Game Seven, until finally faltering, though leaving the game tied after six. In 1988, the Sox were swept by Oakland. Hurst was a 2004 inductee in the Red Sox Hall of Fame. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

TIM WAKEFIELD (1995-2011) … Known for his knuckleball, he captured everyone's attention HIS very first year, with a 14-1 start to the season before running out of steam and finishing 16-8. He secured his 200th Major League victory in 2011. He's started 430 of his 590 Red Sox games and relieved in the other 160, at times contributing key innings to help spare an overworked pitching staff -- for instance, throwing 3 1/3 innings in the midst of the 19-8 blowout of the Red Sox in Game Three of the 2004 American League Championship Series against New York, giving up his scheduled start in Game Four so that the bullpen could be rested for the following day. There can be no telling how important that was as the 2004 Postseason unfolded. Though he got hit hard that day, all in all, his Postseason pitching was at its best against the Yankees. In the 2003 and 2004 American League Championship Series, Wakefield was 3-1 against New York. |

|||

| Video: Tim Wakefield Day at Fenway | |||

|

|

|

|

|

MEL PARNELL (1947-1956) … Recognized in 1997 as an inductee in the Red Sox Hall of Fame, Mel Parnell had the distinction near the end of his 10 seasons with the Red Sox of throwing a no-hitter in Fenway Park in 1956. It was the last one thrown by a Boston lefthander until Jon Lester's in 2008. Parnell really got underway with a 15-8 season in 1948. Many still believe the Red Sox would have had a better chance of going to that year's World Series if it had been Parnell who manager Joe McCarthy picked to pitch the one-game playoff against the Cleveland Indians. In 1949, Parnell further proved himself with a league-leading 25 wins (and 27 complete games) and a 2.77 ERA. Parnell ranks fourth among all Red Sox pitchers with 123 wins. He lost only 75 games. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

JIM LONBORG (1965-1971) … Jim Lonborg was an easy choice for the 1967 American League Cy Young Award. During the wholly unforeseen year of the Impossible Dream, his 22-9 season helped lead the Red Sox from a half-game out of last place the year before to the 1967 AL pennant. The 22 wins led the league, as did his 246 strikeouts. His earned run average was 3.16 In the '67 World Series against St. Louis, Jim was even better. He won Game Two by throwing a one-hitter and in Game Five gave up a total of three hits and one run, earning the win just as convincingly. Despite a Game Seven loss on only two days' rest, he finished the Series with an ERA of 2.63. Over seven seasons, Lonborg won 68 games for the Red Sox with a career ERA of 3.94. After retirement, he and his wife Rosemary would continue to live in Boston and remain avid supporters of the Jimmy Fund. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

RAY COLLINS (1909-1915) … The left-hander from northern Vermont won 84 games in a career spent entirely with the Red Sox before he somewhat inexplicably lost his ability to pitch well and retired at age 28. During his five full and two partial seasons with the Sox, Collins recorded a career earned run average of 2.51, impressive in any era, was a member of the pennant-winning teams of 1912 and 1915, and boasted an ERA of 1.88 in World Series play. His 19-8 record in 1913 ranked him fourth in the league for winning percentage, and his 1914 record of 20-13 made him one of only three AL pitchers to reach the 20-win plateau. Wins #18 and 19 were both achieved on the same day, when he threw two complete games during a doubleheader in Detroit. Collins was also in the top ten in the league for five years in WHIP (walked and hits per innings pitched). |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

LUIS TIANT (1971-1978) … He played eight seasons for the Red Sox in the midst of a 19-year career, and in three of those eight years the Red Sox took the campaign for the pennant to the final day of the year. In 1975, they took the World Series to the seventh game. In 1972, Tiant led the league with a 1.91 earned run average, winning 15 games (15-6), and was a big part of the strike-shortened season which left the Sox just a half-game out of first place. In 1975, he won 18 games in the regular season and was 3-0 in the Postseason, beating the A's in the ALCS and winning Game One and Game Four of the World Series. In 1978, Tiant accounted for 13 of Boston's 99 wins. In three other years, Luis was a 20-game winner for the Red Sox. He's been in the Red Sox Hall of Fame since 1997 and his 122 wins for Boston places him fifth all-time. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

HERB PENNOCK (1915-1922, 1934) … Though Pennock was briefly a member of three pennant-winning teams (Philadelphia in 1914 and Boston in 1915 and 1916), he only threw a total of three innings in two World Series and then missed Boston's 1918 year entirely while serving in the Navy during the First World War. His best year with Boston came in 1919 when he went 16-8 with an ERA of 2.71. During eight seasons in a Red Sox uniform, Pennock won 62 games with a 3.67 ERA before being traded to the New York Yankees where he would win 162 games and go 5-0 in World Series play. Red Sox GM Eddie Collins brought Pennock back to the Red Sox in 1934 for what would be the last of his 22 big league seasons. He was 2-0 with a 3.05 ERA in 62 innings, appearing almost entirely out of the bullpen. He would go on to work as coach for the Red Sox and became head of Minor League operations in 1940. As a Cooperstown inductee, he became a charter member of the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 1995. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

ERNIE SHORE (1914-1917) … A towering Southern farm boy with the mind of an engineer, pitcher Ernie Shore is forever linked with Babe Ruth. Teammates on three clubs and in two World Series, they together tossed what many fans and some historians long considered a perfect game. Tall, rangy, and awkward, young Ernie never liked farming. Setting tobacco with a peg, Shore said later, “just kills your back. It wasn’t for me.” As a teenager he occasionally played outfield for a local team called the Red Strings. In 1910 he enrolled in the preparatory department at Guilford College in Greensboro, N. C., the only Quaker college south of Philadelphia. Shore hoped to become a civil engineer. He would teach mathematics at Guilford in the off-seasons after graduating in 1914. Shore pitched on the college’s baseball squad for five seasons, including two years after he had turned pro—“Guilford being one of the few that allows professionals on its teams (provided the player has made the college team before he enters the professional ranks and makes a certain grade),” Baseball Magazine explained. His coach for four seasons was Chick Doak, later the skipper at the University of North Carolina. Shore’s college record was 38-8-2. New York Giants Manager John McGraw, a famous judge of young talent, asked Doak to send Shore North for a trial in 1912. The Giants thus acquired “the thinnest pitcher in captivity,” the New York Times wrote. He played in 1913 at Greensboro in the North Carolina State League, where Chick Doak was his manager. Shore posted a respectable 11-12 record for the tail-end club. Jack Dunn of Baltimore in the International League then drafted him for $400. Dunn’s 1914 Orioles were considered one of the best minor-league clubs ever assembled. He had “two wonderful pitchers in Ruth and Shore—two more for Connie Mack,” Sporting Life noted. But a new Federal League team in Baltimore siphoned off his fan base, so Dunn quickly sold Shore, pitcher George Herman Ruth, and catcher Ben Egan to the majors. Many expected them to land with Mack’s Athletics, but instead they all went to the Boston Red Sox. Shore's best year with the Red Sox was 1915, when he won 18, lost 8 and compiled a 1.64 earned run average. He was 3–1 in World Series action in 1915 and 1916. He missed the 1918 Red Sox World Championship season, having enlisted in the military in that war year. His most famous game occurred on June 23, 1917, against the Washington Senators in the first game of a doubleheader at Fenway Park. Ruth started the game, walking the first batter, Ray Morgan. As newspaper accounts of the time relate, the short-fused Ruth then engaged in a heated argument with apparently equally short-fused home plate umpire Brick Owens. Owens tossed Ruth out of the game, and the even more enraged Ruth then slugged the umpire a glancing blow before being taken off the field; the catcher Pinch Thomas was also ejected. Shore was recruited to pitch, and came in with very few warmup pitches. With a new pitcher and catcher, runner Morgan tried to steal but was thrown out. Shore then proceeded to retire the remaining 26 Senators without allowing a baserunner, earning a 4–0 Red Sox win. For many years the game was listed in record books as a "perfect game," but officially it is scored as a no-hitter, shared (albeit unequally) by two pitchers. Following the game, Ruth paid a $100 fine, was suspended for ten games, and issued a public apology for his behavior. He entered with the Babe and he left with the Babe. Shore, along with Babe Ruth and many other stars was sold to the New York Yankees by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee, where he closed out his career. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

RED RUFFING (1924-1930) … Ruffing made his major league debut in 1924 with the Boston Red Sox, pitching without a decision over 23 innings of work. He saw regular playing time with the Sox over the next few years but had limited success, garnering a 39–96 record in five-and-a-half years with Boston. However, the Red Sox were in the midst of the darkest period in their history, and Ruffing usually got abysmal run support. His best year, in terms of earned run performance, came in 1928, when he posted a respectable 3.89 ERA. However, even in that year, he only had a 10–25 record. Ruffing's career was revived by a mid-season trade in 1930 which sent him to the New York Yankees for Cedric Durst. This deal is now reckoned as one of the most lopsided trades in baseball history; 1930 proved to be Durst's last year in the majors. Buoyed by the offensive production of greats Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, he won 15 games after the trade despite a hefty 4.14 ERA. Ruffing eventually turned into an ace, winning 20 games or more four times in a row from 1936 to 1939, and striking out a league high 190 batters in 1932. He regularly contended for the ERA crown, twice posting ERAs under 3.00, and appeared in seven World Series. Red Ruffing is a member of The Hall of Fame |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

CARL MAYS (1915-1919) … In a 15-year career he compiled a 207–126 record with 29 shutouts, 862 strikeouts and a 2.92 earned run average when the league average was 3.48. Mays won twenty or more games five times during his career. He was also noted for his skills with a bat, hitting five home runs, recording 110 runs batted in, and sporting a lifetime .268 batting average—an unusually high mark for a pitcher. Mays is the only Red Sox pitcher to toss two nine-inning complete game victories on the same day, as he bested the Philadelphia Athletics 12–0 and 4–1 on August 30, 1918. Those two wins put the Red Sox one step from clinching the league championship, as they led Cleveland by 3 1/2 games with 4 remaining to play. Carl Mays was not a well-liked man, but he was a tremendous pitcher and the game’s only “submariner” in 1918. He came up to Boston from Providence of the International League in 1915, with a fellow rookie named Babe Ruth. By 1916, Mays and Ruth had established themselves as the core of what figured to be a great pitching staff for years to come—Ruth was just 21, Mays was 24 and lefty Dutch Leonard was 24. Leonard was somewhat of a disappointment, but in 1917, Ruth and Mays established themselves as a devastating 1-2 punch at the top of the rotation, as Ruth finished 24-13 with a 2.01 ERA and Mays went 22-9 with a 1.74 ERA.

His lack of popularity, though, always

bothered Mays, and it probably didn’t help that Ruth—despite being boorish

and obnoxious—was such a big hit with fans. Mays

would bark and hold grudges against fielders who missed plays, he would

throw inside at opposing batters and, as one teammate noted, he carried

himself with the disposition of a man with a permanent toothache. In

a Baseball Magazine interview done in 1920, Mays said, “There is such a

thing as popularity. We all know people who are popular without being able

to explain why they should be. We also know people who are not popular,

and yet they may be even more deserving of respect. Popularity does not

necessarily rest on merit. Nor is unpopularity necessarily deserved.” Mays did not become the rotation mainstay he appeared to be for the Red Sox. His career took bizarre twists from there. A bitter dispute with the team in 1919 led to his being sent to the Yankees in the middle of the season. In 1920, he became the only pitcher in baseball history to kill a batter with a pitched ball when an inside fastball struck Cleveland’s Ray Chapman in the head. Mays pitched for the Yankees for four years before he was sent to Cincinnati, and was later accused, according to baseball writer Fred Lieb, of throwing the World Series in 1920 and 1921. (The charges were never made formal or public). He closed out his career with the Reds, finishing with one season with the Giants. He compiled a 207-126 record and a 2.92 ERA over the course of his career. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

TEX HUGHSON (1941-1944, 1946-1949) … Hughson broke in with Boston in 1941 and played all eight of his Major League seasons for the Red Sox before arm troubles brought about a premature end to his career. His second season, 1942, saw him lead the league in wins with a 22-6 record and 113 strikeouts. His 18-5 record in 1944 led the league in winning percentage. Hughson was on the All-Star team three years running, 1942-1944. After a year off to serve during World War II, he came back with another 20-win season, 20-11 (2.75 ERA) in 1946. Those wins helped the Red Sox reach the World Series against the Cardinals, in which he pitched very well in two of his three outings and had a Series ERA of 3.14. He finished his Red Sox career with an excellent 96-54 record and an ERA of 2.94. He was named to the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2002. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

CURT SCHILLING (2004-2008) … Curt Schilling is considered one of the great postseason pitchers of all time, having won a World Series game with three different franchises. His 2004 Game 6 ALCS performance with a sutured tendon dressed in a bloody sock was the defining image in one of baseball's all-time playoff comebacks and an inspiration in overturning an 86-year old World Series drought. Despite being one of the most outspoken and opinionated players in the game, his on-field performance rose when it mattered most. During postseason play, he went 11-2 with a 2.23 ERA and garnered World Series co-MVP and NLCS MVP awards. For his career, he recorded 216 wins and 3,116 strikeouts while only walking 711. The Red Sox acquired Schilling to gain another top-of-the-line starter after their previous season once again ended in heartbreak against their vaunted rivals -- an 11th-inning Game 7 loss to the New York Yankees in the ALCS. Within his contract, Schilling negotiated a $2 million salary bump if he helped the team win the World Series, to go along with an extra year at $13 million. "I guess I hate the Yankees now," Schilling said after being introduced. In his first season with the Red Sox, Schilling led the AL with 21 wins and had a 3.26 ERA. For the third time, he finished second in Cy Young voting -- this time behind Johan Santana.

The Red Sox again faced the Yankees in the ALCS. The Red Sox lost the first three games and faced an incredible obstacle -- no team in MLB history had come back from a 3-0 deficit in a seven-game playoff series. After the Red Sox won Games 4 and 5, Schilling took the mound in Game 6 at Yankee Stadium despite a displaced tendon in his ankle that had to be held together by sutures and which required off-season surgery. With blood soaking through the sock while he was on the mound, Schilling pitched seven innings, allowing only four hits and one run to send the series into a Game 7. When the Red Sox won Game 7, 10-3, they pulled off one of the greatest comebacks in sports history -- Schilling's Game 6 performance serving as the series' inspirational moment. The Red Sox swept the Cardinals in the World Series to win their first championship in 86 years. Schilling pitched Game 2 of that series -- with the help of the same ankle procedure -- and went six innings without allowing an earned run. But Schilling's playoff performance took a toll on the rest of his career. In 2005, he started only three games in April before injuries held him out of action until mid-July. When Schilling returned, he was placed into a closing role, where he stayed until the end of August. Schilling was held out of postseason action, and the Red Sox were swept in three games in the ALDS by the Chicago White Sox. For the season, he pitched 93.1 innings, with a 5.62 ERA and nine saves. The following season Schilling bounced back to go 15-7 as a starter, with a 3.97 ERA. The Red Sox, however, went 86-76 and missed out on the postseason. In 2007 Schilling's career appeared to be coming to an end. The Red Sox weren't willing to negotiate a new contract with him, and there was some talk of retirement. While injuries hindered his regular season, he almost pulled off his first career no-hitter against the Oakland Athletics on June 7. With two outs in the ninth inning, Shannon Stewart lined a single into right field. At 40 years old, he would have been the fourth oldest pitcher to pull off the feat behind Randy Johnson, Cy Young and Nolan Ryan. In 151 innings on the season, Schilling went 9-8 with a 3.87 ERA and 101 strikeouts. Against the Angels in the ALDS, he pitched seven innings of scoreless ball and garnered a win. Against the Indians in the ALCS, he went 1-0 in 11.2 innings with a 5.40 ERA. In Game 2 of the World Series against the Colorado Rockies, he picked up a win by going 5.1 innings and giving up one run on four hits. That performance would prove his last major league appearance. The Red Sox swept the Rockies to win their second World Series in four seasons. Schilling signed a one-year deal with the Red Sox for 2008, but because of shoulder troubles didn't appear in a single regular-season game. During the off-season, he announced his retirement on March 23, 2009, on his blog. He retired as the only pitcher to win a World Series start for three different teams. In the regular season, he compiled a record of 216-146, 83 complete games, 3.46 ERA, 3,261 inning and 3,116 strikeouts. In the postseason, he went 11-2 with a 2.23 ERA with four complete games. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

DENNIS ECKERSLEY (1978-1984, 1998) … Eckersley began his career in Boston in 1978 with a 20-8 record and a 2.99 ERA. "The Eck" matched the 2.99 ERA in 1979 but was hindered by the support of a third-place team and held to 17 wins (17-10). During his eight seasons with the Red Sox, he worked almost exclusively as a starting pitcher and won 88 games with an ERA of 3.92. A 1984 trade sent Eckersley to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for Bill Buckner. In 1987, the Eck was converted to a reliever in Oakland and began to rack up the saves that propelled the six-time All-Star to Cooperstown. In 1997, 14 years removed from his last game in a Red Sox uniform, Eckersley signed with his former club for what would be the last of his 24 Major League seasons. He went 4-1 with a 4.76 ERA. In 2004, he was inducted into both the National Baseball Hall of Fame and the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame. In his post-playing career, Eckersley has made a name for himself as an insightful and candid TV commentator on NESN and TBS. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

LEFTY GROVE (1934-1941) … After nine seasons with the Philadelphia Athletics, one of the first moves that GM Eddie Collins made for new Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey was to acquire the stellar southpaw, Lefty Grove. Grove had led the league in strikeouts every one of his first seven seasons, and in 1933 he had just completed his seventh season in a row of winning 20 or more games, including a 31-4 season in 1931. In four of the years he led the league in wins. When he arrived in Boston, though, he had some arm problems and struggled through an 8-8 season in 1934 before going 20-12 in 1935. Beginning that year, Grove led the American League in earned run average in four of the next five seasons and had 83 wins against 41 losses. He earned his 300th career win wearing a Red Sox uniform, and finished his career at 300-141 with a lifetime 3.06 ERA. Grove entered the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1947. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

DUTCH LEONARD (1913-1918) … Hubert "Dutch" Leonard was a member of three World Championship clubs for the Red Sox: 1915, 1916, and 1918. However, his very best season for Boston was his second, 1914. In that year, Leonard put up a 19-5 record with the best ERA of any pitcher in the history of 20th and 21st century baseball: 0.96. His time with the Red Sox produced a won/loss record of 90-64 and a 2.13 career ERA. Leonard had an even-better record in the World Series, throwing one complete-game victory in 1915 and one complete-game victory in 1916. He was 2-0 in World Series play with a combined ERA of 1.00.

Left-hander Dutch Leonard had far more

potential than he wound up showing over the course of his 11 seasons in

big-league baseball. He was brought up by the Red Sox in 1913, posting a

14-17 record but a very good ERA of 2.39. It was in his second season that

Leonard flashed his true potential, when he went 19-5 with a 0.96 ERA,

which remains a record for modern baseball. But Leonard didn’t seem to

care for baseball much. He routinely showed up for camp overweight, and

was known for his late-night carousing. He had good reason not to care

much—he owned a successful grape farm in the Fresno area, and only wanted

to use baseball as a way to gain publicity for his raisins. After his

masterpiece of a ’14 season, Leonard settled into a career of

good-but-not-great seasons, frequent injuries and only occasional

brilliance. Not surprisingly, he turned to bending the rules. He

showed up for spring training in 1918 late and out of shape—manager Ed

Barrow had Leonard jogging while wearing the, “rubber shirt,” a spring

training tradition for overweight players. Leonard struggled badly in the

early season. In a start against Cleveland on May 21, the Indians

complained that Leonard was using licorice spit to load up the baseballs.

Dutch Leonard with the Red Sox in 1916. (Photo courtesy of the Library of

Congress.) Indeed, Leonard did become a spitball pitcher, and when

baseball eventually banned the use of the pitch, Leonard was one of the 17

players who was “grandfathered” in and allowed to throw spitballs after

the ban. On June 22, Leonard left the Red Sox and signed with the Fore River shipyard in Quincy, Mass. It was good timing. Two days later, he was moved up to Class 1A. He did not play again in 1918, finishing with an 8-6 record and a 2.72 ERA, his worst to date. He was, in September, nabbed by the army as the War Department began cracking down on ballplayers who took refuge in shipyards. But Leonard was never sent to the front. Nor did he pitch for Boston again. He was traded to Detroit after the season, and closed out his career with five mediocre seasons with the Tigers |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

JOE WOOD (1908-1915) … From 1909 to 1915, he was an overwhelming presence for the Boston Red Sox, winning 116 games in seven seasons and going 34-5 and 1912. Three times he had season earned run averages under well under 2.00. The Red Sox had few pitching worries in those days: They had another excellent young pitcher, Babe Ruth, and the reliable Eddie Cicotte, a future conspirator in the 1919 Chicago Black Sox scandal. Rube Foster and Ernie Shore also had a some outstanding seasons. Wood thrived in such talented company. He went 3-1 in the 1912 World Series, his only post-season appearances as a pitcher. That season he threw only 7 wild pitches in 344 innings, and in 1915 his earned run average was an astounding 1.49. He struck out 2.34 batters for each walk. But he had a frustratingly short pitching career, effectively just those seven magic seasons. An arm injury caused by a broken thumb proved to be too much. Moving to Cleveland in 1917, he tried to switch to the outfield, but it was too late. He just couldn’t bat as well as he had pitched, although he did have a .282 career batting average. By 1923 he was finished. His lifetime earned run average of 2.03 is the fourth best in baseball history. He threw a no-hitter in 1911 and once struck out 15 men in one game. His ratio of hits per game, 7.13, is in the all-time top 15. So is his career won-lost percentage, .672. There is no denying that those are Hall of Fame numbers, and that they were all earned in the so-called modern era of baseball. No statistical excuses for Joe Wood. Both Walter Johnson and Satchel Paige rated Wood the hardest-throwing pitcher they had ever seen. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

BABE RUTH (1914-1919) … Known more for his batting, Babe Ruth broke in with the Red Sox as a left-handed starter in 1914. He won 89 games and lost 46, his career 2.19 ERA still ranking him fourth all-time among Red Sox pitchers. In Ruth's second season, 1915, he was 18-8, but manager Bill Carrigan correctly concluded that he didn't need him to pitch in that year's World Series in order to secure a victory. The Sox won the Series again in 1916, getting there in large part thanks to Ruth's 23-12 season and his league-leading 1.75 ERA. His nine shutouts led the league, as well. In the 1916 World Series, he pitched all 14 innings of Game Two, winning the game 2-1. Ruth shut out the Cubs in Game One of the 1918 Series and threw seven shutout innings on his way to winning Game Four 3-2. For 43 years, Ruth held the record for his 29 2/3 consecutive scoreless World Series innings. He was 3-0 for the Red Sox with a combined 0.87 ERA in Postseason play. In 1918, Ruth's 11 home runs led the American League, as he played 59 games in the outfield when not pitching. In 1919, he played outfield much more than he pitched, hitting 29 homers while going 9-5 with a 2.97 ERA and leading the league in RBI (114). After the season, his contract was sold to the New York Yankees. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1936. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

ROGER CLEMENS (1984-1996) … "The Rocket" holds the Major League record for strikeouts in a game with 20. He stunned the baseball world when he first attained it in 1986 before replicating the total 10 years later. Clemens is tied with Cy Young for the most wins of any pitcher in Red Sox franchise history: 192 (with 111 defeats). He had a 3.06 earned run average in his 13 years with the Red Sox and was a five-time All-Star during his days with Boston. Clemens was a three-time Cy Young Award winner with the Red Sox in 1986, 1987, and 1991, and won the MVP in 1986, as well. Needless to say, he led the league in numerous categories during the top years, the very best of which was probably 1986 when he was 24-4 with a 2.48 ERA and had 258 strikeouts. That year was the first of seven seasons in which Clemens led the league in ERA, four of which were for Boston. Clemens struck out 2,590 opponents while pitching for the Red Sox. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

PEDRO MARTINEZ (1998-2004) … Pedro’s first start in a Boston uniform came against the A’s in Oakland on Opening Day. He fanned 11 in seven shutout innings in a 2-0 victory. The next day, the Red Sox sold 15,000 tickets for future games. Pedro's second start, at Seattle, was another masterpiece. By the time he returned to Boston for his home debut, the town was abuzz. Pedro slowed down in May after getting slugged by an intestinal problem. Boston fans, feeling he lacked toughness, booed him and complained about his fat contract. They soon changed their tune. Pedro returned in June, battled through a tired arm down the stretch and finished with a 19-7 record and a 2.89 ERA. in 1999, all the stars were aligned for Pedro to have his best year ever. From his first start to his last, he had it all working. In what ranks among the most remarkable seasons ever, Pedro went 23-4 with a 2.07 ERA—during a campaign that saw the most scoring since 1936. The league average ERA was almost three runs higher than Pedro's. The runner-up to the ERA title, David Cone, was at 3.44. Pedro whiffed 313, which not only led the AL, but made him the first pitcher ever to reach that plateau in both leagues. Behind Pedro's stunning performance, the Red Sox managed to shadow the Yankees all year, but fell four wins short of a division title. Boston easily took the Wild Card, with a 94-68 record. The highlight of the regular season for Boston fans came at Yankee Stadium in September, when Pedro dismantled the Bronx Bombers with a 17-strikeout, one-hit gem. No one had ever struck out that many Yankees. A homer by Chili Davis accounted for New York’s lone tally. Pedro also had a memorable appearance in the All-Star Game. In front of the faithful at Fenway, he struck out Barry Larkin, Larry Walker and Sammy Sosa in the first inning, and then fanned Mark McGwire to start the second. Matt Williams reached on an error, but Pedro struck out Jeff Bagwell and Pudge Rodriguez threw out Williams trying to steal. Another big day for Pedro was August 31, when he and his brother Ramon were reunited. The Red Sox had signed the older Martinez that spring, hoping he would recover from shoulder surgery in time to help them down the stretch. Ramon joined the club in time for the playoffs and won two games in September. In the 1999 ALCS against the Yankees, Pedro started Game 3 and dominated again without his best stuff. He allowed just two hits and struck out 12 in seven innings, humiliating the Bronx Bombers 13-1. Sadly for Red Sox fans, that was their team’s first win of the series—and last of the year. New York had scored a pair of one-run victories to open the series and finished off Boston 9-2 and 6-1 to capture the pennant in five games. The following season was an opportunity missed for Pedro and the Red Sox. Laboring through shoulder soreness, he still ptiched to a microscopic 1.74 ERA. No other starter in the league finished with a mark under 3.00. Pedro was tops in the AL in shutouts with four, strikeouts with 284, and batting average allowed at .167. His 18-6 record was the only thing keeping his team in the mix most of the campaign. Pedro, in his prime at 29, had full command of all his pitches and was just as tough on hitters when he didn’t have his 98 mph heater. His best game came against the D-Rays at the end of August, when he took a no-hitter into the ninth. Tamps Bay's John Flaherty broke up the no-no, which Pedro won 8-0. The 2001 season found Williams under intense pressure. Unfortunately, the number-one man, Pedro, could not stay off the DL. After a great 7-1 start, he began to lose velocity in June and went on the shelf for July and most of August with a slight tear in his rotator cuff. It was an injury similar to the one that cut short Ramon’s career, though less serious. Confident he could still dominate hitters without a mid-90s fastball, Pedro focused on doing whatever it took to give the Red Sox a complete season in 2002. There were no complaints about Pedro, who pitched great ball all year. He went 20-4, led the league with a 2.26 ERA and 239 strikeouts, and his .833 winning percentage was the best in baseball. Pedro's command was so good that he could put hitters away with any one of his pitches. Boston's plan for 2003 was to plug holes. The offense carried the load for most of the year. Ortiz, Millar, Varitek, Ramirez, Garciaparra and Nixon each hit at least 25 homers, and Mueller edged New York's Derek Jeter for the batting title. Pedro contributed 14 wins and a 2.22 ERA in 29 starts. The Division Series opened in Oakland. The A’s touched Pedro for three runs, but the Red Sox came back to take a 4-3 lead. Oakland tied it in the ninth and won in the 12th against Lowe. Back in Oakland for the decider, Pedro took the mound and hurled seven solid innings. The A’s led 1-0 going into the sixth, but Boston scored four times off Barry Zito. The bullpen held on for a 4-3 win to advance. The Red Sox got their long-awaited postseason rematch with the Yankees in the ALCS. Wakefield won Game 1, but Andy Pettitte beat Lowe the next evening to even the series. Pedro battled Roger Clemens in Game 3 at Fenway. With emotions running particularly high, he threw a beanball at Karim Garcia, and the benches emptied. Pedro spotted Don Zimmer charging at him, sidestepped the Yankee bench coach, and tossed him to the ground. The incident enraged New York fans, as did a gesture Pedro directed at Jorge Posada. He pointed to his head, indicating that the Yankees catcher was next on his list. New York eventually got the better of Pedro with a 4-3 victory, but the fireworks didn't end. Clemens threw close to Ramirez as payback, and the Boston outfielder's overreaction created another fracas. Later in the game, Garcia hopped the righ tfield fence and teamed with Jeff Nelson to pummel a member of the Boston groundskeeping crew. Boston captured two of the next three to force a Game 7 in New York, with Pedro on the mound against Clemens again. The Red Sox chased the Rocket in the second inning, but Mike Mussina came in to control the damage. Pedro was up 5-2 after seven hard-fought innings. Little then made a fateful decision to send him out for the eighth. After Pedro retired Nick Johnson, hits by Jeter and Bernie Williams made the score 5-3. Little walked out to the mound and asked his ace if he had anything left. Pedro said yes and stayed in to face Hideki Matsui. He doubled, and the Jorge Posada did the same to make it 5-5. The Yankees won it in the 11th on a homer by Bret Boone off Wakefield. Little was fired 11 days later. The 2004 season was played under the usual cloud of Yankee dominance. Curt Schilling was now in the starting rotation, along with Pedro, Wakefield, Lowe and young Bronson Arroyo. Keith Foulke, the former Oakland closer, was signed to anchor the bullpen. The Red Sox went on a tear in September to give the Yankees a scare and wrap up the Wild Card. Pedro finished the year at 16-9 with an uncharacteristic 3.90 ERA. Still, he averaged better than a strikeout per inning, and hitters managed just a .238 average against him. Schilling, who went 21-6, became the Boston ace. In the Division Series, Pedro got a win as Boston swept the Angels to set up another ALCS meeting with the Yankees. In Game 1, Schilling took the mound on a sore ankle and was beaten 8-7. Red Sox hopes faded further in Game 2 as Pedro lost 3-1. Game 3 was a complete embarassment, as New York bombed Boston 19-8. The Red Sox stole Game 4, tying it against Mariano Rivera in the 9th and then winning it in the 12th on an Ortiz homer. Then it was all Red Sox, as Damon and Ortiz hit early homers and Lowe redeemed his so-so season with a great outing in a 10-3 win. It marked the first-time in post-season history that a team down 0-3 had come back to win it all. The World Series, between the Red Sox and St. Louis Cardinals, figured to be a hitter’s showcase. Pedro hurled seven shutout innings in Game 3, striking out six and retiring the last 14 hitters he faced. He escaped his only real trouble in the first when Ramirez gunned down Larry Walker at the plate on a short fly ball. The Boston outfielder, who hit .417 against St. Louis, was named the World Series MVP. |

|||